One morning, just after dawn had spread its first pale light, I was walking along the streets of Sardarpara in Rangpur city. The weary body of the city seemed to be rinsed by a greyish glow. Then, all of a sudden, my eyes caught a small child sitting by the roadside, wearing a shirt mottled with red and yellow patches. Behind him, on the wall, a torn poster was hung with half-crumpled words that read: “Bring change, start with yourself.”

I stopped my walking for a while. Not merely because of the poster, but because of the boy’s shirt. Because of the way the poster’s words were twisted. And because of a question that suddenly began to stir in my mind like a rising storm. And that is: why do we need to think?

Why is it necessary to think?

I felt that in our daily lives, we walk, eat, work, watch, listen, and write almost mechanically. But how many things do we truly watch, hear or write?

To watch is not just to have something pass before our eyes. To listen is not merely to let sounds enter our ears. Real watching and listening require perceptions. It is an inner act of understanding. That is where, the need to think emerges. Thinking means stepping into the depths of what we watch or listen—and asking questions from some broader aspects in order to observe and analyze the whole scenario with our minds. And then, framing the ways of solutions or better improvements.

For instance, when I looked at the boy’s shirt, a thought came to me: did he choose it himself? Or was it an old garment donated by someone? And that slogan on the poster—“Start with yourself”—was it simply a catchy line for publicity? Or was it a genuine call to action? If we don’t think, if we don’t pause to questions like these, how will we ever tell the difference between truth and fabrication?

I can recall: when I was in school, one of my teachers once told me, “If you don’t think, you will be used. If you think, you will become creative one.”

Now I can realize—we are living in an age of being used. The narcissism-infected feeds of social media, dazzling advertisements, the loud flags of wavering ideologies, the inflated numbers of so-called online ‘public opinion’—all are carefully arranged for us.

To get rid of these arrangements and think for oneself means to seek the truth in one’s own way—or at least to take attempts.

But how does one think?

In my view, the first step to think is—to raise questions—whether you understand the whole subject or not.

For example, when I saw that the boy’s shirt, questions emerged: Where does he live? Does he go to school? Where are his parents? What do they do?

Each question takes me deeper—into the city’s economic system, into the politics of deprivation, into the twisting turns of our social structure.

The second step is to look and listen everything without any veil or filter.

In reality, most of what we watch today is what someone wants us to watch. From the filtered contents of social media and the carefully chosen headlines of online media outlets, and the way how educational syllabuses are designed in our country—everything is shaped to make us watch, listen, and understand in a certain way.

If you learn to ‘read’ the roadside poster or the child’s shirt for yourself, you may step beyond the control of those, who is scripting reality for you likely. Your thinking may even cross the limits of convention.

The third, and perhaps most vital, step is— to cultivate the courage to doubt.

We believe on many things—what our families have taught us, what teachers have told us, what popular leaders have preached. But, when someone truly engages in deep thinking, they not only believe but also raise questions.

Though we have to keep in mind that doubt does not refer to disbelief, it is simply an extended form of thinking. Because thinking is not only about going deep into a matter—it is also, in a sense, an ethical act for establishing social well-being.

A person without thinking may become lifeless. In addition, a thoughtless society may become cruel. In such a society, conscience and the sense of life become shackled. So, when someone is beaten on the street, or starves, or loses everything— people may simply sigh and say “Oh dear!”

But if we start to practise thinking, questions would arise: Why is this deprivation occurring? Who are responsible for this?

From that angle, thinking awakens our humanity. Without thinking, we do not raise questions. Without questions, our conscience does not respond to society’s flaws. Without a sensitive conscience, there is no real constructive change.

After all, every transformation begins with a movement inside the mind—and the habit of deep, meticulous thinking is what sparks that movement. Thus, we have to think in order to establish social well-being, justice and peace.

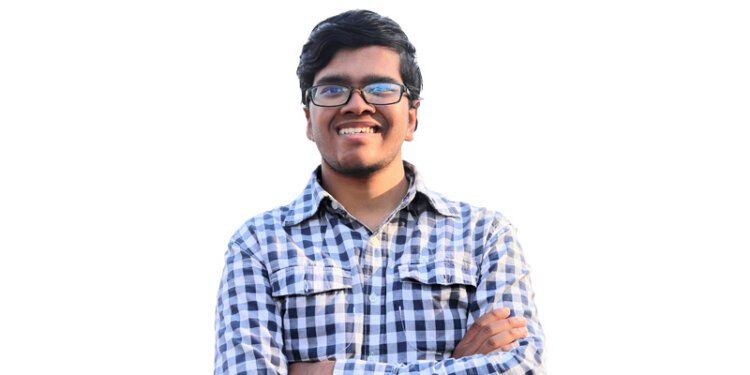

Rusaid Ahmed is working with The Catchline as a Special Correspondent from Rangpur, Bangladesh. He is also a freelance journalist who regularly contributes columns to leading national dailies in both Bengali and English, covering national and international affairs. Alongside journalism, he writes poetry, short stories, and feature articles for various media outlets. Passionate about language, he also enjoys translating literary and journalistic works. He can be reached at: rusaidahmed02@gmail.com