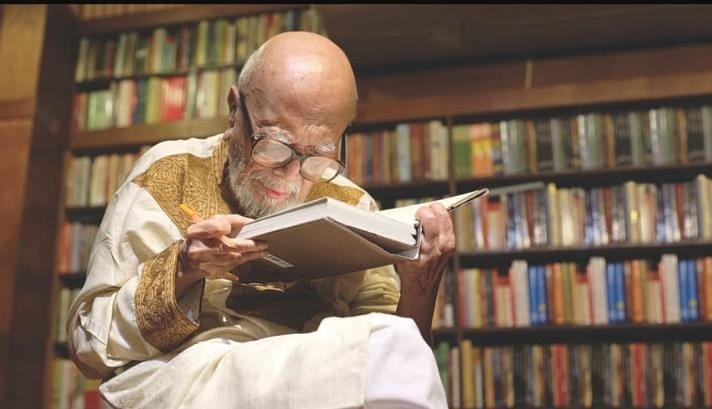

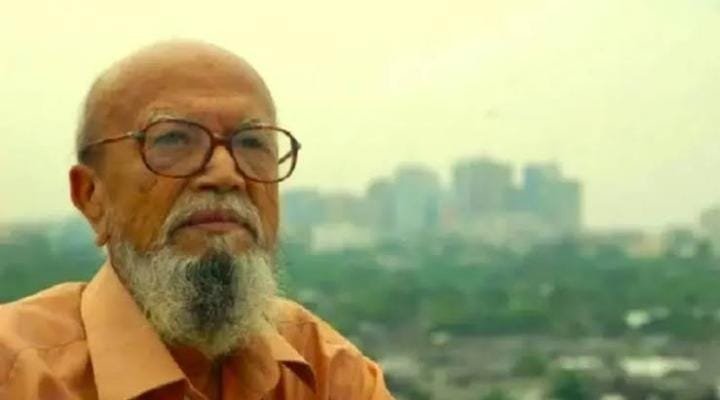

The name of the late poet Al Mahmud is not an ordinary one in the arena of Bangla literature. During the mid-20th century, he portrayed the rural landscape of Bangladesh in literature—particularly in poetry analyzing the eternal folk culture of Bengal and the relationships between men and women, which were absent in other works then.

Despite receiving the Bangla Academy Award, Ekushey Padak, and other honors for his literary contributions, very little discussion, research, and analysis have been done on the broader scope of his works in the country’s literary-cultural circles.

While a large number of eminent literary critics and researchers have focused on the works of Rabindranath Tagore and Kazi Nazrul Islam, they have rarely shed similar light on Al Mahmud.

Distinct Poetic Voice

In the 1950s and 1960s, when most poets and writers of then-East Bengal imitated the literary styles of Nazrul and Tagore, Al Mahmud emerged with a distinctively Bangladeshi poetic language. Drawing sustenance from the sights, tastes, and countless elements of folk culture from the villages of Bangladesh, he gifted the nation with modern poems through collections like ‘Lok-Lokantar’, ‘Kaler Kolos’, and ‘Sonali Kabin’.

Example from Lok-Lokantar

In his poem ‘Protno’, he writes:

“…sometimes the edge of monsoon, sometimes the arrow of stone,/ adornments of women in collective life, and more—/ standing here, you may imagine as much as you like/ how intimately history is tied to your blood.…”

This illustrates the poet’s sense of history and his love for culture.

Example from Sonali Kabin

In Sonali Kabin—a sonnet sequence—he portrays rural life, traditions, and relationships with unmatched intimacy:

“…Whose ruse holds you clad in a sapphire-blue sari?/ Melted by ascetic’s devotion, the color of night spills over,/… Should you feel shy, I shall with tireless, wet kisses/ erase the initials, the blood-red ancient un-Aryan script.…”

Here, Al Mahmud evokes ancient imagery, folk culture, and egalitarian resistance against injustice and oppression.

Political and Social Engagement

The political and social transformations of his time strongly influenced Al Mahmud’s writing.

1969 Mass Uprising

During the people’s uprising against Ayub Khan, he wrote in ‘Unosottorer Chhora-1’:

“Truck! Truck! Truck!/ The pig-faced truck will come,/ lock the door tight!/ Why should we lock the doors, pull the bolts shut?/ Asad has gone with the procession,/ the procession will return!”

This reflects his patriotic and protest-driven spirit.

1952 Language Movement

Recalling the Language Movement, in ‘Ekusher Kobita’ he wrote:

“On the 21st of February,/ at the noon hour,/ rain falls, but what rain?/ It is Barkat’s blood.… Don’t you recognize the golden boy?/ Don’t you recognize Khudiram?/ Who, breath held, gave his life/ to buy the free air?…”

Here, nationalist sentiment is fused with secular humanist ideals.

Post-Independence Shift

In post-independence Bangladesh, Al Mahmud’s worldview shifted. After imprisonment for anti-government writings, he began exploring global religious scriptures.

Works such as ‘Mayabi Porda Dule Otho’, ‘Odrishtobadider Rannabanna’, and ‘Bakhtiarer Ghora’ reflected this transformation. For example, in ‘Deyal Theke Kotha’, he wrote:

“Someone speaks from the wall, Joseph, Joseph!/ You were the man who explained the king’s dream?/ No, I am not Joseph, no. I don’t know who Pharaoh is, merely/ I have reddened my eyes with the marks of my own dreams.…”

Religious imagery, Islamic consciousness, and historical identity began shaping his works—sparking debate but not diminishing his poetic strength.

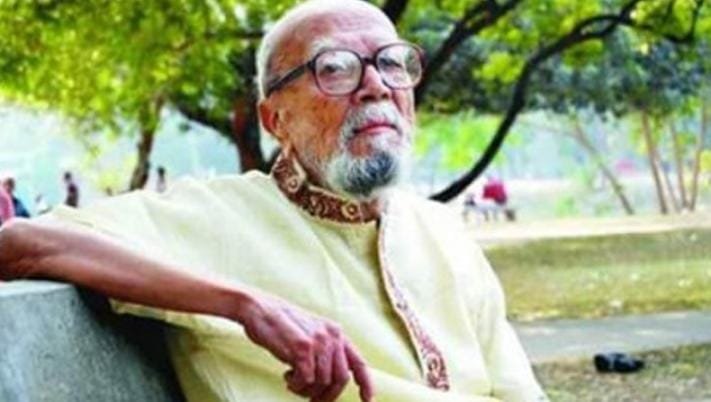

Legacy and Need for Research

Even with ideological shifts, Al Mahmud’s writings consistently intertwined:

-

Ancient Bengali life

-

Colonial and Pakistan-era struggles

-

Aspirations of independent Bangladesh

His verse “The tyrant flees through the back door” resurfaced in the 2024 anti-discrimination movement, appearing in chants and graffiti.

This underlines the urgent necessity of establishing a dedicated research institute on Al Mahmud—similar to the Kazi Nazrul Institute or International Rabindra Research Institute—to academically study his works.

Because to build an independent, sovereign, and discrimination-free Bangladesh, there is no alternative but to study Al Mahmud.